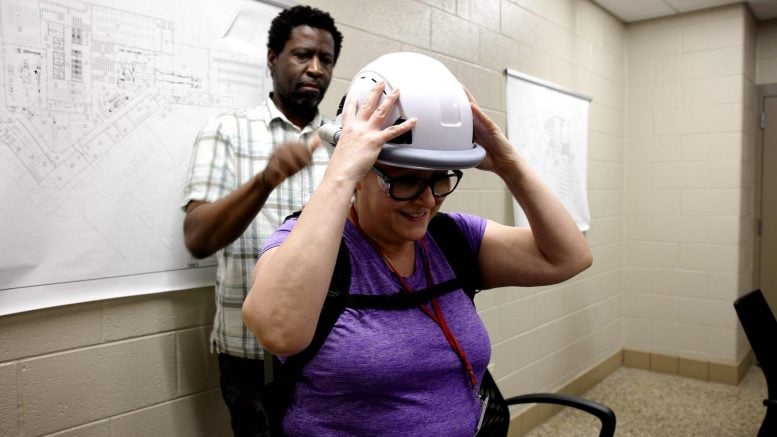

Herek Clack, U-M associate professor of civil and environmental engineering and co-founder of Taza Aya, helps Michigan Turkey Producers employee Blanca Chaidez adjust a helmet that will protect her from infectious aerosols with an air curtain rather than a face mask. Credit: Jeremy Little, Michigan Engineering

Headworn tech from a University of Michigan startup could protect agricultural and industrial workers from airborne pathogens.

Taza Aya has created a hard hat with an air curtain that prevents nearly all aerosols from reaching the face, using nonthermal

Independent, third-party testing of Taza Aya’s device showed the effectiveness of the air curtain, curved to encircle the face, coming from nozzles at the hat’s brim. But for the air curtain to effectively protect against pathogens in the room, it must first be cleansed of pathogens itself. Previous research by the group of Taza Aya co-founder Herek Clack, U-M associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, showed that their method can remove and kill 99% of airborne viruses in farm and laboratory settings.

“Our air curtain technology is precisely designed to protect wearers from airborne infectious pathogens, using treated air as a barrier in which any pathogens present have been inactivated so that they are no longer able to infect you if you breathe them in,” Clack said. “It’s virtually unheard of—our level of protection against airborne germs, especially when combined with the improved ergonomics it also provides.”

Harnessing Nonthermal Plasma for Pathogen Removal

Fire has been used throughout history for sterilization, and while we might not usually think of it this way, it’s what’s known as a thermal plasma. Nonthermal, or cold, plasmas are made of highly energetic, electrically charged molecules and molecular fragments that achieve a similar effect without the heat. Those ions and molecules stabilize quickly, becoming ordinary air before reaching the curtain nozzles.

Taza Aya’s Worker Wearable Protection device keeps airborne virus particles from reaching a workers mouth and nose with an air curtain. That air is pre-treated to kill any viruses. Credit: Jeremy Little, Michigan Engineering

Prototype Development and Specifications

Taza Aya’s prototype features a backpack, weighing roughly 10 pounds, that houses the nonthermal plasma module, air handler, electronics, and the unit’s battery pack. The handler draws air into the module, where it’s treated before flowing to the air curtain’s nozzle array.

Taza Aya’s Worker Wearable Protection device keeps airborne virus particles from reaching a workers mouth and nose with an air curtain. That air is pre-treated to kill any viruses. Credit: Jeremy Little, Michigan Engineering

Response to COVID-19 and Agriculture Challenges

Taza Aya’s progress comes in the wake of the

An animation screenshot shows a simulated worker wearing a hardhat connected by two air tubes to a backpack that houses the device’s cold plasma module. Air is shown flowing downward from the brim of the hat. Credit: Jeremy Little, Michigan Engineering