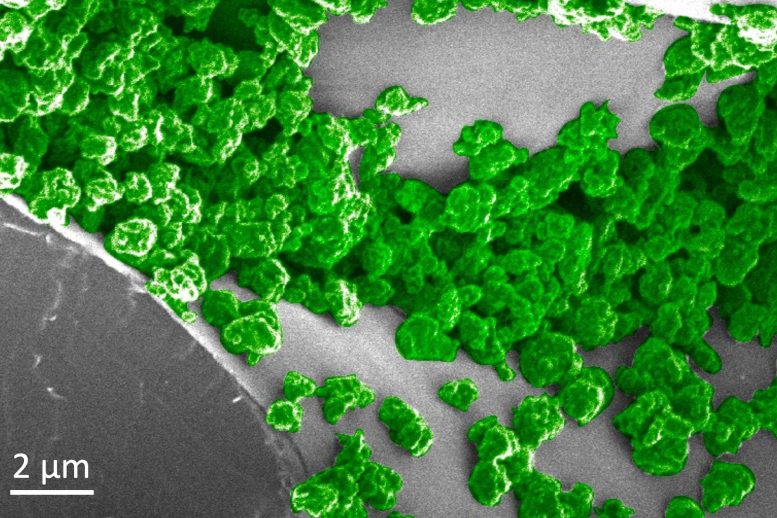

Using specialized nanoparticles embedded in plant leaves, MIT engineers have created a novel light-emitting plant that can be charged by an LED. In this image, the green parts are the nanoparticles that have been aggregated on the surface of spongy mesophyll tissue within the plant leaves. Credit: Courtesy of the researchers

Using nanoparticles that store and gradually release light, engineers create light-emitting plants that can be charged repeatedly.

Using specialized nanoparticles embedded in plant leaves,

“We wanted to create a light-emitting plant with particles that will absorb light, store some of it, and emit it gradually,” says Michael Strano, the Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT and the senior author of the new study. “This is a big step toward plant-based lighting.”

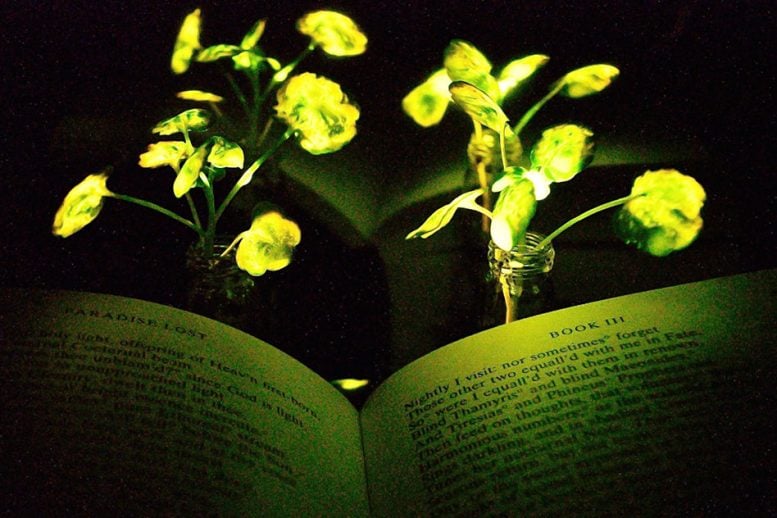

Illumination of a book (“Paradise Lost,” by John Milton) with the first generation of nanobionic light-emitting plants. Credit: Seon-Yeong Kwak

“Creating ambient light with the renewable chemical energy of living plants is a bold idea,” says Sheila Kennedy, a professor of architecture at MIT and an author of the paper who has worked with Strano’s group on plant-based lighting. “It represents a fundamental shift in how we think about living plants and electrical energy for lighting.”

The particles can also boost the light production of any other type of light-emitting plant, including those Strano’s lab originally developed. Those plants use nanoparticles containing the enzyme luciferase, which is found in fireflies, to produce light. The ability to mix and match functional nanoparticles inserted into a living plant to produce new functional properties is an example of the emerging field of “plant nanobionics.”

Pavlo Gordiichuk, a former MIT postdoc, is the lead author of the new paper, which appears in Science Advances.

Light capacitor

Strano’s lab has been working for several years in the new field of plant nanobionics, which aims to give plants novel features by embedding them with different types of nanoparticles. Their first generation of light-emitting plants contained nanoparticles that carry luciferase and luciferin, which work together to give fireflies their glow. Using these particles, the researchers generated watercress plants that could emit dim light, about one-thousandth the amount needed to read by, for a few hours.

In the new study, Strano and his colleagues wanted to create components that could extend the duration of the light and make it brighter. They came up with the idea of using a capacitor, which is a part of an electrical circuit that can store electricity and release it when needed. In the case of glowing plants, a light capacitor can be used to store light in the form of photons, then gradually release it over time.

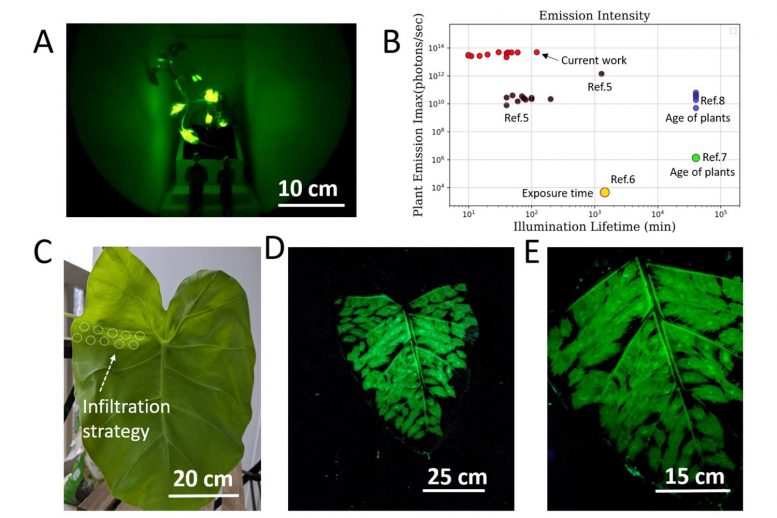

After 10 seconds of charging, plants can glow brightly for several minutes, and they can be recharged repeatedly. Credit: Courtesy of the researchers

To create their “light capacitor,” the researchers decided to use a type of material known as a phosphor. These materials can absorb either visible or ultraviolet light and then slowly release it as a phosphorescent glow. The researchers used a compound called strontium aluminate, which can be formed into nanoparticles, as their phosphor. Before embedding them in plants, the researchers coated the particles in silica, which protects the plant from damage.

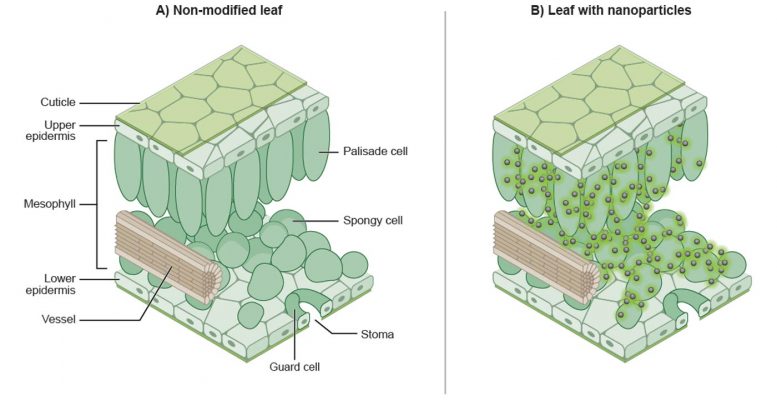

The particles, which are several hundred nanometers in diameter, can be infused into the plants through the stomata — small pores located on the surfaces of leaves. The particles accumulate in a spongy layer called the mesophyll, where they form a thin film. A major conclusion of the new study is that the mesophyll of a living plant can be made to display these photonic particles without hurting the plant or sacrificing lighting properties, the researchers say.

This film can absorb photons either from sunlight or an LED. The researchers showed that after 10 seconds of blue LED exposure, their plants could emit light for about an hour. The light was brightest for the first five minutes and then gradually diminished. The plants can be continually recharged for at least two weeks, as the team demonstrated during an experimental exhibition at the Smithsonian Institute of Design in 2019.

Researchers showed that they could illuminate the leaves of a plant called the Thailand elephant ear, which can be more than a foot wide — a size that could make the plants useful as an outdoor lighting source. Credit: Courtesy of the researchers

“We need to have an intense light, delivered as one pulse for a few seconds, and that can charge it,” Gordiichuk says. “We also showed that we can use big lenses, such as a Fresnel lens, to transfer our amplified light a distance more than one meter. This is a good step toward creating lighting at a scale that people could use.”

“The Plant Properties exhibition at the Smithsonian demonstrated a future vision where lighting infrastructure from living plants is an integral part of the spaces where people work and live,” Kennedy says. “If living plants could be the starting point of advanced technology, plants might replace our current unsustainable urban electrical lighting grid for the mutual benefit of all plant-dependent species — including people.”

Large-scale illumination

The MIT researchers found that the “light capacitor” approach can work in many different plant species, including basil, watercress, and tobacco, the researchers found. They also showed that they could illuminate the leaves of a plant called the Thailand elephant ear, which can be more than a foot wide — a size that could make the plants useful as an outdoor lighting source.

The researchers also investigated whether the nanoparticles interfere with normal plant function. They found that over a 10-day period, the plants were able to photosynthesize normally and to evaporate water through their stomata. Once the experiments were over, the researchers were able to extract about 60 percent of the phosphors from plants and reuse them in another plant.

Researchers in Strano’s lab are now working on combining the phosphor light capacitor particles with the luciferase nanoparticles that they used in their 2017 study, in hopes that combining the two technologies will produce plants that can produce even brighter light, for longer periods of time.

Reference: “Augmenting the living plant mesophyll into a photonic capacitor” by Pavlo Gordiichuk, Sarah Coleman, Ge Zhang, Matthias Kuehne, Tedrick T. S. Lew, Minkyung Park, Jianqiao Cui, Allan M. Brooks, Karaghen Hudson, Anne M. Graziano, Daniel J. M. Marshall, Zain Karsan, Sheila Kennedy and Michael S. Strano, 8 September 2021, Science Advances.DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abe9733

The research was funded by Thailand Magnolia Quality Development Corp., a Professor Amar G. Bose Research Grant, MIT’s Advanced Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program, the Singapore Agency of Science, Research, and Technology, a Samsung scholarship, and a German Research Foundation research fellowship.