Researchers at Columbia University have developed Re6Se8Cl2, a superatomic semiconductor that outperforms silicon in speed and efficiency by forming unique quasiparticles. This discovery paves the way for exploring new materials in semiconductor technology.

Columbia chemists discover ballistic flow in a quantum material, a finding which could help overcome shortcomings in semiconductors

Semiconductors, particularly silicon, are fundamental to the operation of various electronic devices such as computers, cellphones, and the device you’re currently using. Despite their widespread use,

In experiments run by the team, acoustic exciton-polarons in Re6Se8Cl2 moved fast—twice as fast as electrons in silicon—and crossed several microns of the sample in less than a nanosecond. Given that polarons can last for about 11 nanoseconds, the team thinks the exciton-polarons could cover more than 25 micrometers at a time. And because these quasiparticles are controlled by light rather than an electrical current and gating, processing speeds in theoretical devices have the potential to reach femtoseconds—six orders of magnitude faster than the nanoseconds achievable in current Gigahertz electronics. All at room temperature.

“In terms of energy transport, Re6Se8Cl2 is the best semiconductor that we know of, at least so far,” Delor said.

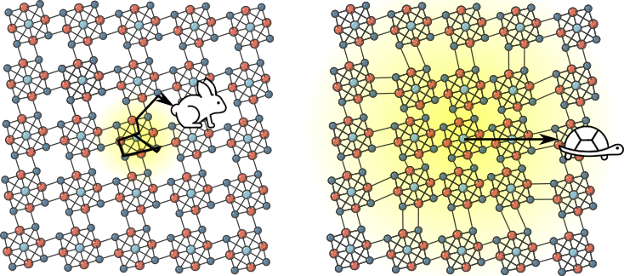

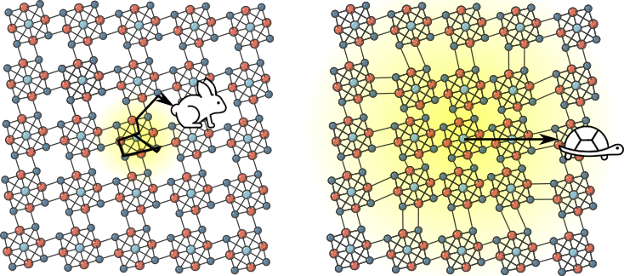

A Quantum Version of the Tortoise and the Hare

Re6Se8Cl2 is a superatomic semiconductor created in the lab of collaborator Xavier Roy. Superatoms are clusters of atoms bound together that behave like one big

What makes silicon a desirable semiconductor is that electrons can move through it very quickly, but like the proverbial hare, they bounce around too much and don’t actually make it very far, very fast in the end. Excitons in Re6Se8Cl2 are, comparatively, very slow, but it’s precisely because they are so slow that they are able to meet and pair up with equally slow-moving acoustic phonons. The resulting quasiparticles are “heavy” and, like the tortoise, advance slowly but steadily along. Unimpeded by other phonons along the way, acoustic exciton-polarons in Re6Se8Cl2 ultimately move faster than electrons in silicon. Credit: Jack Tulyag, Columbia University

Tulyag and his peers in the Delor group spent the next two years working to pinpoint why Re6Se8Cl2 showed such remarkable behavior, including developing an advanced microscope with extreme spatial and temporal resolution that can directly image polarons as they form and move through the material. Theoretical chemist Petra Shih, a PhD student working in Timothy Berkelbach’s group, also developed a quantum mechanical model that provides an explanation for the observations.

The new quasiparticles are fast, but, counterintuitively, they accomplish that speed by pacing themselves—a bit like the story of the tortoise and the hare, Delor explained. What makes silicon a desirable semiconductor is that electrons can move through it very quickly, but like the proverbial hare, they bounce around too much and don’t actually make it very far, very fast in the end. Excitons in Re6Se8Cl2 are, comparatively, very slow, but it’s precisely because they are so slow that they are able to meet and pair up with equally slow-moving acoustic phonons. The resulting quasiparticles are “heavy” and, like the tortoise, advance slowly but steadily along. Unimpeded by other phonons along the way, acoustic exciton-polarons in Re6Se8Cl2 ultimately move faster than electrons in silicon.

The Semiconductor Search Continues

Like many of the emerging quantum materials being explored at Columbia, Re6Se8Cl2 can be peeled into atom-thin sheets, a feature that means they can potentially be combined with other similar materials in the search for additional unique properties. Re6Se8Cl2, however, is unlikely to ever make its way into a commercial product—the first element in the molecule, Rhenium, is one of the rarest on earth and extremely expensive as a result.

But with the new theory from the Berkelbach group in hand along with the advanced imaging technique that Tulyag and the Delor group developed to directly track the formation and movement of polarons in the first place, the team is ready to see if there are other superatomic contenders capable of beating Re6Se8Cl2’’s speed record.

“This is the only material that anyone has seen sustained room-temperature ballistic exciton transport in. But we can now start to predict what other materials might be capable of this behavior that we just haven’t considered before,” said Delor. “There is a whole family of superatomic and other 2D semiconductor materials out there with properties favorable for acoustic polaron formation.”

Reference: “Room-temperature wavelike exciton transport in a van der Waals superatomic semiconductor” by Jakhangirkhodja A. Tulyagankhodjaev, Petra Shih, Jessica Yu, Jake C. Russell, Daniel G. Chica, Michelle E. Reynoso, Haowen Su, Athena C. Stenor, Xavier Roy, Timothy C. Berkelbach and Milan Delor, 26 October 2023, Science.DOI: 10.1126/science.adf2698

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.