Researchers warn of the potential social, ethical, and legal consequences of technologies interacting heavily with human brains.

Surpassing the biological limitations of the brain and using one’s mind to interact with and control external electronic devices may sound like the distant cyborg future, but it could come sooner than we think.

Researchers from Imperial College London conducted a review of modern commercial brain-computer interface (BCI) devices, and they discuss the primary technological limitations and humanitarian concerns of these devices in APL Bioengineering, from AIP Publishing.

The most promising method to achieve real-world BCI applications is through electroencephalography (EEG), a method of monitoring the brain noninvasively through its electrical activity. EEG-based BCIs, or eBCIs, will require a number of technological advances prior to widespread use, but more importantly, they will raise a variety of social, ethical, and legal concerns.

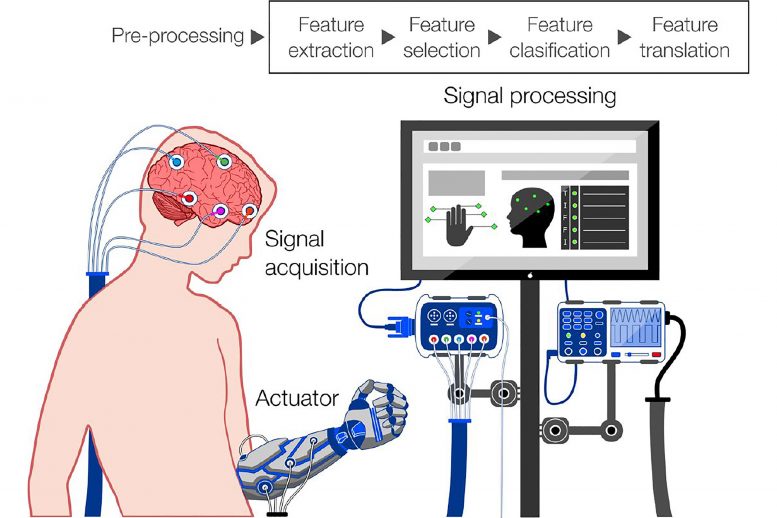

A schematic demonstrates the steps required for eBCI operation. EEG sensors acquire electrical signals from the brain, which are processed and outputted to control external devices. Credit: Portillo-Lara et al.

Though it is difficult to understand exactly what a user experiences when operating an external device with an eBCI, a few things are certain. For one, eBCIs can communicate both ways. This allows a person to control electronics, which is particularly useful for medical patients that need help controlling wheelchairs, for example, but also potentially changes the way the brain functions.

“For some of these patients, these devices become such an integrated part of themselves that they refuse to have them removed at the end of the clinical trial,” said Rylie Green, one of the authors. “It has become increasingly evident that neurotechnologies have the potential to profoundly shape our own human experience and sense of self.”

Aside from these potentially bleak mental and physiological side effects, intellectual property concerns are also an issue and may allow private companies that develop eBCI technologies to own users’ neural data.

“This is particularly worrisome, since neural data is often considered to be the most intimate and private information that could be associated with any given user,” said Roberto Portillo-Lara, another author. “This is mainly because, apart from its diagnostic value, EEG data could be used to infer emotional and cognitive states, which would provide unparalleled insight into user intentions, preferences, and emotions.”

As the availability of these platforms increases past medical treatment, disparities in access to these technologies may exacerbate existing social inequalities. For example, eBCIs can be used for cognitive enhancement and cause extreme imbalances in academic or professional successes and educational advancements.

“This bleak panorama brings forth an interesting dilemma about the role of policymakers in BCI commercialization,” Green said. “Should regulatory bodies intervene to prevent misuse and unequal access to neurotech? Should society follow instead the path taken by previous innovations, such as the internet or the smartphone, which originally targeted niche markets but are now commercialized on a global scale?”

She calls on global policymakers, neuroscientists, manufacturers, and potential users of these technologies to begin having these conversations early and collaborate to produce answers to these difficult moral questions.

“Despite the potential risks, the ability to integrate the sophistication of the human mind with the capabilities of modern technology constitutes an unprecedented scientific achievement, which is beginning to challenge our own preconceptions of what it is to be human,” Green said.

Reference: “Mind the gap: State-of-the-art technologies and applications for EEG-based brain-computer interfaces” by Roberto Portillo-Lara, Bogachan Tahirbegi, Christopher A.R. Chapman, Josef A. Goding and Rylie A. Green, 20 July 2021, APL Bioengineering.DOI: 10.1063/5.0047237