A team from Duke University has created a speech prosthetic that translates brain signals into speech, aiding individuals with neurological disorders. While still slower than natural speech, the technology, backed by advanced brain sensors and ongoing research, shows promising potential for enhanced communication abilities. (Artist’s concept) Credit: SciTechDaily.com

A prosthetic device deciphers signals from the brain’s speech center to predict what sound a person is trying to say.

A team of neuroscientists, neurosurgeons, and engineers from Duke University have developed a speech prosthetic that can convert brain signals into spoken words.

The new technology, detailed in a recent paper published in the journal

A device no bigger than a postage stamp (dotted portion within white band) packs 128 microscopic sensors that can translate brain cell activity into what someone intends to say. Credit: Dan Vahaba/Duke University

Imagine listening to an audiobook at half-speed. That’s the best speech decoding rate currently available, which clocks in at about 78 words per minute. People, however, speak around 150 words per minute.

The lag between spoken and decoded speech rates is partially due to the relatively few brain activity sensors that can be fused onto a paper-thin piece of material that lays atop the surface of the brain. Fewer sensors provide less decipherable information to decode.

Enhancing Brain Signal Decoding

To improve on past limitations, Cogan teamed up with fellow Duke Institute for Brain Sciences faculty member Jonathan Viventi, Ph.D., whose biomedical engineering lab specializes in making high-density, ultra-thin, and flexible brain sensors.

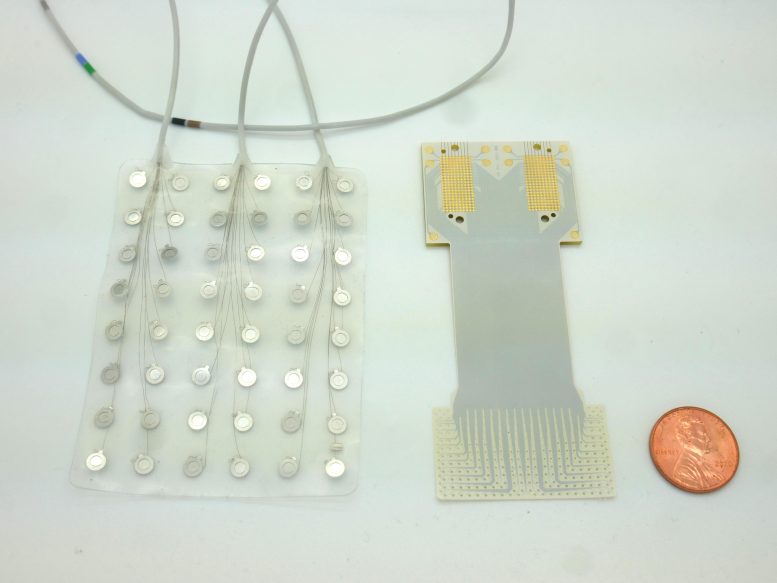

Compared to current speech prosthetics with 128 electrodes (left), Duke engineers have developed a new device that accommodates twice as many sensors in a significantly smaller footprint. Credit: Dan Vahaba/Duke University

For this project, Viventi and his team packed an impressive 256 microscopic brain sensors onto a postage stamp-sized piece of flexible, medical-grade plastic. Neurons just a grain of sand apart can have wildly different activity patterns when coordinating speech, so it’s necessary to distinguish signals from neighboring brain cells to help make accurate predictions about intended speech.

Clinical Trials and Future Developments

After fabricating the new implant, Cogan and Viventi teamed up with several Duke University Hospital neurosurgeons, including Derek Southwell, M.D., Ph.D., Nandan Lad, M.D., Ph.D., and Allan Friedman, M.D., who helped recruit four patients to test the implants. The experiment required the researchers to place the device temporarily in patients who were undergoing brain surgery for some other condition, such as treating Parkinson’s disease or having a tumor removed. Time was limited for Cogan and his team to test drive their device in the OR.

“I like to compare it to a NASCAR pit crew,” Cogan said. “We don’t want to add any extra time to the operating procedure, so we had to be in and out within 15 minutes. As soon as the surgeon and the medical team said ‘Go!’ we rushed into action and the patient performed the task.”

The task was a simple listen-and-repeat activity. Participants heard a series of nonsense words, like “ava,” “kug,” or “vip,” and then spoke each one aloud. The device recorded activity from each patient’s speech motor cortex as it coordinated nearly 100 muscles that move the lips, tongue, jaw, and larynx.

Afterward, Suseendrakumar Duraivel, the first author of the new report and a biomedical engineering graduate student at Duke, took the neural and speech data from the surgery suite and fed it into a

In the lab, Duke University Ph.D. candidate Kumar Duraivel analyzes a colorful array of brain-wave data. Each unique hue and line represent the activity from one of 256 sensors, all recorded in real-time from a patient’s brain in the operating room. Credit: Dan Vahaba/Duke University