Lab tests show promise for reducing jet noise in commercial and military aviation.

Aerospace engineers at the University of Cincinnati and the Naval Research Laboratory have come up with a new nozzle design for F-18 fighter planes they hope will dampen the deafening roar of the engines without hindering performance.

Distinguished professor Ephraim Gutmark, an Ohio Eminent Scholar, and his students in UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science designed and tested the new nozzles on 1/28th-scale jet engines in his aeroacoustics lab.

The interior of the nozzles features triangular fins like rows of shark teeth that significantly reduced jet engine noise in UC lab tests. The project is a collaboration between UC, the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory and Naval Air Station Patuxent River. This fall NAVAIR will test the UC designs and performance on F-18 Super Hornets, the tactical fighter plane used by the U.S. Marines and Navy.

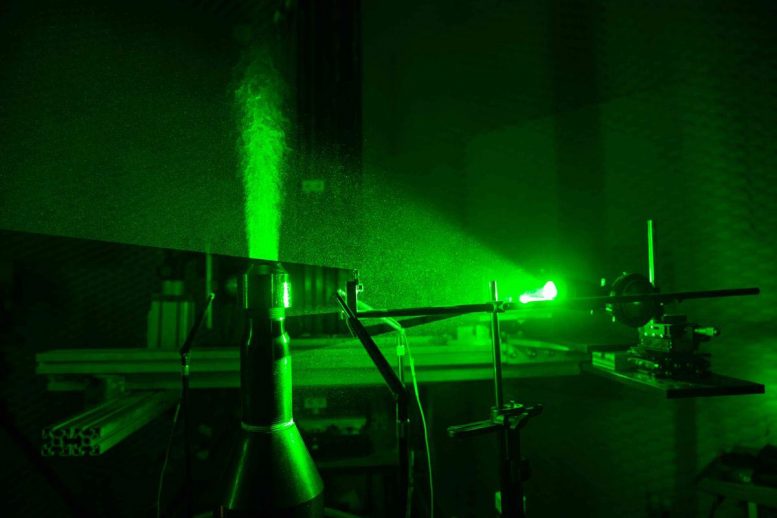

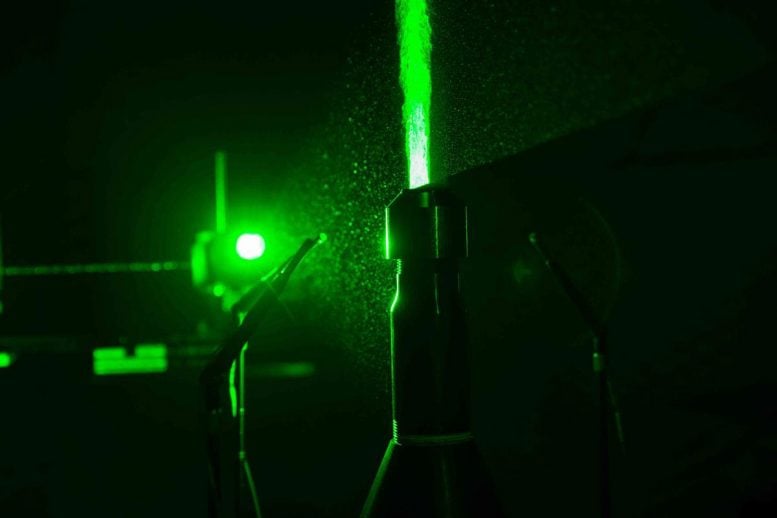

Lasers illuminate the plume of a scale-model jet engine used aboard F-18 Super Hornets. UC developed a new engine nozzle that muffles the noise from jet engines without hindering performance. Credit: Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

“They’re simple attachments that change the behavior of the flow coming out of the engine with minimal effect on its performance,” Gutmark said.

UC’s lab tests showed the new nozzle could reduce engine noise by between 5 and 8 decibels. That might not seem like much. But unlike linear scales like a ruler where an inch is always an inch, decibels are measured in a logarithmic scale in which 20 decibels is tenfold louder noise.

“That’s very significant,” Gutmark said. “Typically, engine companies are happy even getting a half-decibel improvement because decibels represent a logarithmic scale.”

UC College of Engineering and Applied Science doctoral student Mohammad Saleem holds one of the novel jet engine nozzles UC designed in professor Ephraim Gutmark’s lab. The U.S. Navy will test UC’s design on F-18 Super Hornets this fall. Credit: Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

UC’s preliminary lab results hold promise for reducing jet noise in both commercial and military aviation. UC and the Navy applied for a joint patent.

“If the design works with this engine, it can be applied to any other engine with very minor modification,” Gutmark said.

The project was funded under the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Environmental Research Program.

Hearing loss and tinnitus are the leading causes of military disability claims, affecting more than 2.6 million former service members, according to numbers from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The VA spends more than $1 billion per year on hearing loss cases, which represent about 15% of new disability claims filed with the VA each year.

UC’s research holds promise to reduce the health and safety impact of jet noise on commercial and military aviation. Here a flight crew aboard the USS Ronald Reagan wears ear protection while helping to launch and land F/A-18 Super Hornets. Credit: Gray Gibson/U.S. Navy

Jet noise in particular represents a serious health risk in military and commercial aviation. According to the Naval Research Advisory Committee, Navy personnel on flight decks are exposed to noise in excess of 150 decibels.

“On aircraft carriers the crew that works with pilots on the flight deck needs to be very close to the plane when it takes off. Because of the short runway on the carrier, they must operate the engine with afterburners, so it’s very loud,” Gutmark said.

Jets are so loud that the noise and vibrations can affect even the aircraft itself — a phenomenon called acoustic loading, Gutmark said.

“By suppressing the noise, you are helping the crew but also helping the longevity of the airplane itself,” Gutmark added.

“It’s a thrill to know you’re working on fighter planes. There’s a cool factor.”

— Mohammad Saleem, UC aerospace engineering student

UC has been working on the project with the Naval Research Lab and NAVAIR for two years. The Navy provides computational analysis and aircraft information to complement UC’s design and experimental work.

Gutmark’s diverse research has included engine combustion and propulsion technology, acoustics and even biomedical research. He taught aerospace engineering principles to pilots in the U.S. Navy’s Strike Fighter Tactics Instructor program, the school that inspired the movie “Top Gun.”

“It was exciting to teach them because they were really interested,” Gutmark said. “They really wanted to know more about what happens when the plane does this or that. And getting feedback from someone who understands what the plane is doing practically when they’re flying was a special opportunity.”

UC doctoral students Mohammad Saleem and Aatresh Karnam work on scale models of F-18 Super Hornet jet engines in UC’s aeroacoustics lab. Credit: Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Students in Gutmark’s lab wear industrial-grade ear protection when working with the jet engines in a subterranean lab in Rhodes Hall. The engines are mounted to the ground inside an anechoic chamber — a room designed to completely absorb reflections of acoustic waves. Students can turn on jet engines remotely outside the chamber and use a suite of sensors to measure and analyze the noise from the exhaust plumes.

“In our lab we have four different measurement techniques, including signal processing through acoustics and optical measurements and laser equipment,” UC doctoral student Aatresh Karnam said. “Like any engineering field, you have to adapt multiple techniques to know what data to capture, how to process it and how to interpret it. That’s a difficult challenge.”

An array of sensitive microphones surrounds the jet in the chamber. Perhaps not surprisingly, the noise sounds different depending on one’s relative position to the jet plume.

“Each one of these components of noise is propagating in different directions,” professor Gutmark said. “The microphones are distributed in an arc around the jet so we can detect noise that is going downstream or upstream or sideways.”

UC aerospace engineering students use lasers and other equipment to observe and measure noise and the exhaust plume from a scale-model jet engine used in F-18 Super Hornets. Credit: Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

UC engineers test their novel nozzle designs on both cold and heated jets with exhaust that burns as hot as 1,100 degrees

UC doctoral student Mohammad Saleem holds up several custom jet engine nozzles he helped design in UC professor Ephraim Gutmark’s lab. Credit: Andrew Higley/UC Creative + Brand

Saleem said he has always been interested in aerospace engineering. But he enjoys the challenge presented by such a complicated project as jet engine noise.

“I chose UC because it’s a strong school in propulsion systems,” he said.

But he admits his friends and family are impressed when he talks about working with F-18 Super Hornets.

“It’s a thrill to know you’re working on fighter planes. There’s a cool factor,” Saleem said.

“Engineering is about problem solving. The joy is coming up with a system that works. I think that’s satisfying.”