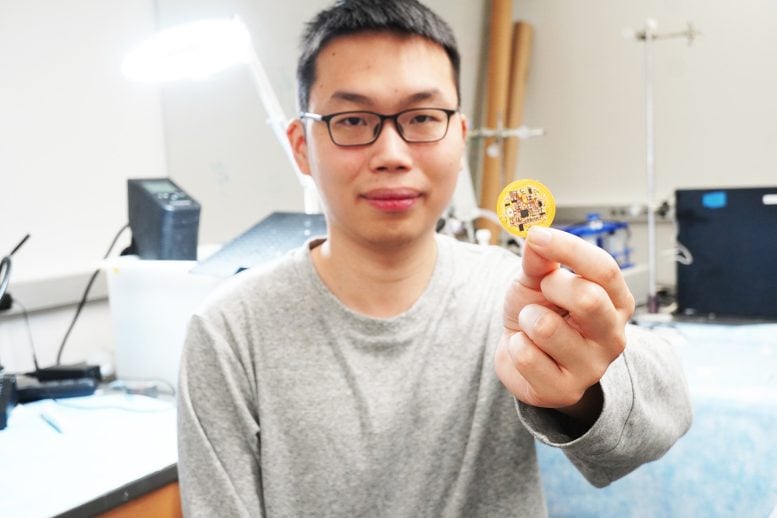

Jiuyun Shi holds a small device he and a team of University of Chicago scientists invented that integrates living cells, gel, and sensors to create “living bioelectronics” to heal the skin. Credit: Jiuyun Shi and Bozhi Tian/University of Chicago

Scientists develop flexible, adaptable, and storable patch that combines bacteria and sensors to interface with the body.

Researchers have created “living bioelectronics,” a device combining cells, gel, and electronics to monitor and treat skin conditions. Tested on mice, the device reduces inflammation and holds potential for broader medical applications. The team is working to commercialize the technology.

For many years, Professor Bozhi Tian’s laboratory has been exploring how to meld the realms of electronics—typically rigid, metallic, and bulky—with the soft, flexible, and delicate nature of the human body. In their most recent research, they have created a prototype for what they call “living bioelectronics”: a combination of living cells, gel, and electronics that can integrate with living tissue.

The patches are made of sensors, bacterial cells, and a gel made from starch and gelatin. Tests in mice found that the devices could continuously monitor and improve psoriasis-like symptoms, without irritating skin.

“This is a bridge from traditional bioelectronics, which incorporates living cells as part of the therapy,” said Jiuyun Shi, the co-first author of the paper and a former PhD student in Tian’s lab (now with Stanford University).

“We’re very excited because it’s been a decade and a half in the making,” said Tian.

The researchers hope the principles can also be applied to other parts of the body, such as cardiological or neural stimulation. The study is published May 30 in Science.

A Third Layer

Pairing electronics with the human body has always been difficult. Though devices like pacemakers have improved countless lives, they have their drawbacks; electronics tend to be bulky and rigid, and can cause irritation.

But Tian’s lab specializes in uncovering the fundamental principles behind how living cells and tissue interact with synthetic materials; their previous work has included a tiny pacemaker that can be controlled with light and strong but flexible materials that could form the basis of bone implants. In this study, they took a new approach. Typically, bioelectronics consists of the electronics themselves, plus a soft layer to make them less irritating to the body.

But Tian’s group wondered if they could add new capabilities by integrating a third component: living cells themselves. The group was intrigued with the healing properties of certain bacteria such as S. epidermidis, a microbe that naturally lives on human skin and has been shown to reduce inflammation.

A wafer-thin patch incorporates a flexible electronic circuit, a gel made from tapioca starch and gelatin, and friendly bacteria that help treat skin conditions. Credit: Jiuyun Shi and Bozhi Tian/University of Chicago

They created a device with three components. The framework is a thin, flexible electronic circuit with sensors. It is overlaid with a gel created from tapioca starch and gelatin, which is ultrasoft and mimics the makeup of tissue itself. Lastly, S. epidermidis microbes are tucked into the gel. When the device is placed on skin, the bacteria secrete compounds that reduce inflammation, and the sensor monitors the skin for signals like skin temperature and humidity.

In tests with mice prone to psoriasis-like skin conditions, there was a significant reduction in symptoms.

Their initial tests ran for a week, but the researchers hope the system—which they term the ABLE platform, for Active Biointegrated Living Electronics—could be used for a half-year or more. To make the treatment more convenient, they said, the device can be freeze-dried for storage and easily rehydrated when needed.

Since the healing effects are provided by microbes, “It’s like a living drug—you don’t have to refill it,” said Saehyun Kim, the other co-first author of the paper and a current PhD student in Tian’s lab.

Broader Applications and Future Goals

In addition to treating psoriasis, the scientists can envision applications such as patches to speed wound healing on patients with diabetes.

They also hope to extend the approach to other tissue types and cell types. “For example, could you create an SciTechDaily