While SHEIN has its origins in China it is one of the biggest shopping apps in the United States, SHAREit has been banned in India despite being massively popular elsewhere, and Likee is chasing TikTok—but desperate to avoid a similar fate.

China’s app makers are having to be agile in a world where key markets have turned hostile to their country’s tech.

They are either going under the radar in territories where the war over privacy, security and geopolitics rages—or are moving to friendlier markets to win millions of downloads.

Experts say that could signal an unstoppable rise for China’s smart and responsive tech, depending on the long-term damage that security and diplomatic squabbles may bring to the Made in China brand.

For now, the strategies of Chinese-owned platforms—quick reflexes to their customer base and aggressive social media marketing—are winning fans in unexpected places.

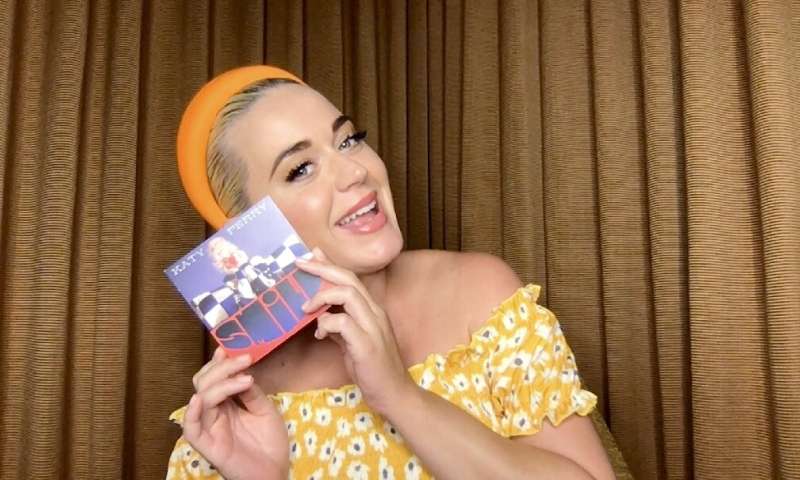

Fast-fashion online retailer SHEIN has deployed a legion of influencers and celebrities in the US, including singers Rita Ora and Katy Perry, to soar up the app store rankings.

The platform also advertised a Perry-curated range of affordable tees, dresses and accessories to coincide with her album launch this year.

The company now boasts one of the top five free shopping apps on Apple’s app store in the US, Australia and France, according to US-based research agency Sensor Tower.

“Many of their global users will actually be unaware that they are dealing with a Chinese company,” Hong Kong-based retail analyst Philip Wiggenraad said of such apps.

In a February post on WeChat to recruit suppliers, SHEIN said it had operations spanning more than 200 countries, with 2019 sales exceeding 20 billion yuan ($2.96 billion).

Catch me if you can

Even TikTok, battered by an ownership dispute in the US where it is accused of being a security risk, has racked up around 800 million installs this year globally despite the squall of negative publicity, Sensor Tower data shows.

That comes despite its blacklisting in India, which has also banned more than 200 other Chinese apps in the wake of a deadly border dispute earlier this year.

TikTok is now struggling to close a deal allowing it to continue its massively popular US operations.

The travails of the app—and others winded in the geopolitical ruckus—may signpost the way ahead for other less well-known Chinese platforms.

File-sharing app SHAREit, banned in June by India, has quickly pivoted to new markets.

It says it already has 20 million monthly active users in South Africa and is also targeting Indonesia, which has the world’s fourth-largest population.

Others are basing outside China and experts say tying in early with western businesses could balance against potential boycotts by suspicious governments.

“We have servers in several different locations across the globe, including the United States, Singapore and India,” a spokesperson for Bigo, owner of short-video app Likee, told AFP.

“But we do not have any servers in mainland China or Hong Kong.”

Bigo was built and headquartered in Singapore before being bought by Chinese firm JOYY, which is listed on the Nasdaq in New York. The app was the third-most installed by a Chinese publisher for the year to mid-September, according to Sensor Tower.

Adapt or die?

With privacy, cybersecurity and potential influence by Beijing all hot-button issues, Chinese developers will need to do a lot more to convince governments and consumers in the long term.

Suspicions will likely “change the landscape in which they operate, and force them to adopt very different business and data localisation strategies”, said Severine Arsene of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

That could mean locating a company’s headquarters and tech development in “safer” territories, or locating data processing in different territories.

“This requires adapting the whole tech architecture of a given service,” she added.

The pressure points to the fundamental issue of Chinese companies being seen as “de facto proxies” of the Chinese Communist Party, says Hinrich Foundation research fellow Alex Capri.

“Chinese firms will find it increasingly difficult to compete outside of a techno-authoritarian digital landscape,” he added.

Chinese companies have increasingly drawn suspicion over whether they might be compelled to share data with the government.

Despite recent spats with Washington and New Delhi, Beijing has shown no signs of “putting aside its technology ambitions”, said United Overseas Bank economist Ho Woei Chen.

Even a future decoupling of China from the global tech supply chain could have the unintended consequence of forcing “Chinese companies to upgrade and build up their capabilities”, she added.

And buffed up by a vast domestic market, “they will likely remain in business”.