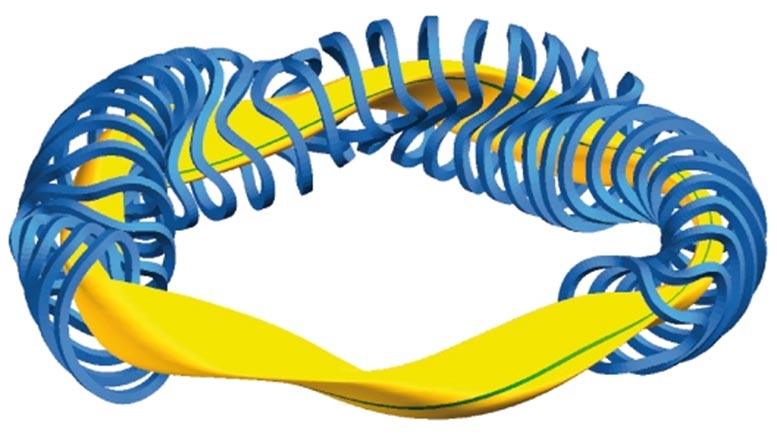

Wendelstein 7-X stellarator schema. Credit: Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics

Stellarators, twisty magnetic devices that aim to harness on Earth the fusion energy that powers the sun and stars, have long played second fiddle to more widely used doughnut-shaped facilities known as tokamaks. The complex twisted

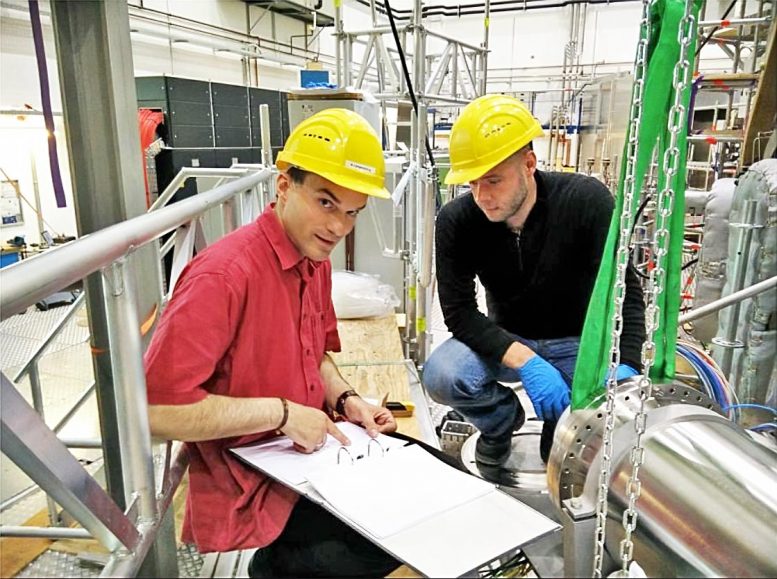

PPPL physicist Novimir Pablant with computer simulation of W7-X magnetic coils and plasma. Credit: Photo of Pablant and collage by Elle Starkman/Office of Communications. Computer simulation courtesy of IPP

A recent report on W7-X findings in Nature magazine confirms the success of the efforts of designers to shape the intricately twisted stellarator magnets to reduce neoclassical transport. First author of the paper was physicist Craig Beidler of the IPP Theory Division. “It’s really exciting news for fusion that this design has been successful,” said Pablant, a coauthor along with Langenberg of the paper. “It clearly shows that this kind of optimization can be done.”

David Gates, head of the Advanced Projects Department at PPPL that oversees the laboratory’s stellarator work, was also highly enthused. “It’s been very exciting for us, at PPPL and all the other U.S. collaborating institutions, to be part of this really exciting experiment,” Gates said. “Novi’s work has been right at the center of this amazing experimental team’s effort. I am very grateful to our German colleagues for so graciously enabling our participation.”

Carbon-free power

The fusion that scientists seek to produce combines light elements in the form of plasma — the hot, charged state of matter composed of free electrons and atomic nuclei, or ions, that makes up 99 percent of the visible universe — to generate massive amounts of energy. Producing controlled fusion on Earth would create a virtually inexhaustible supply of safe, clean, and carbon-free source of power to generate electricity for humanity and serve as a major contributor to the transition away from fossil fuels.

IPP physicist Andreas Langenberg, left, and PPPL physicist Novimir Pablant before installation of the XICS diagnostic on the W7-X. Credit: Photo by Scott Massida

Stellarators, first constructed in the 1950s under PPPL founder Lyman Spitzer, can operate in a steady state with little risk of the