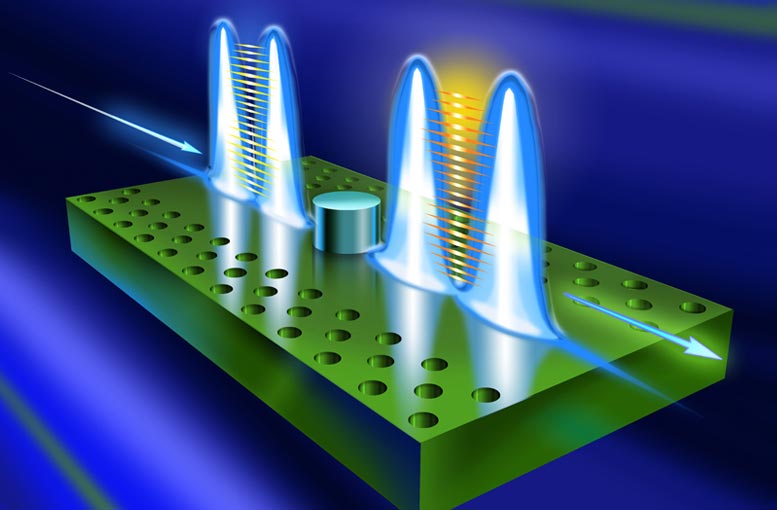

Jung-Tsung Shen, associate professor in the Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering, has developed a deterministic, high-fidelity, two-bit quantum logic gate that takes advantage of a new form of light. This new logic gate is orders of magnitude more efficient than the current technology. Credit: Jung-Tsung Shen

An efficient two-bit quantum logic gate has been out of reach, until now.

Research from the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis has found a missing piece in the puzzle of optical quantum computing.

Jung-Tsung Shen, associate professor in the Preston M. Green Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering, has developed a deterministic, high-fidelity two-bit quantum logic gate that takes advantage of a new form of light. This new logic gate is orders of magnitude more efficient than the current technology.

“In the ideal case, the fidelity can be as high as 97%,” Shen said.

His research was published in May 2021 in the journal Physical Review A.

The potential of quantum computers is bound to the unusual properties of superposition — the ability of a quantum system to contain many distinct properties, or states, at the same time — and entanglement — two particles acting as if they are correlated in a non-classical manner, despite being physically removed from each other.

Where voltage determines the value of a bit (a 1 or a 0) in a classical computer, researchers often use individual electrons as “qubits,” the quantum equivalent. Electrons have several traits that suit them well to the task: they are easily manipulated by an electric or magnetic field and they interact with each other. Interaction is a benefit when you need two bits to be entangled — letting the wilderness of quantum mechanics manifest.

But their propensity to interact is also a problem. Everything from stray magnetic fields to power lines can influence electrons, making them hard to truly control.

For the past two decades, however, some scientists have been trying to use photons as qubits instead of electrons. “If computers are going to have a true impact, we need to look into creating the platform using light,” Shen said.

Photons have no charge, which can lead to the opposite problems: they do not interact with the environment like electrons, but they also do not interact with each other. It has also been challenging to engineer and to create ad hoc (effective) inter-photon interactions. Or so traditional thinking went.

Less than a decade ago, scientists working on this problem discovered that, even if they weren’t entangled as they entered a logic gate, the act of measuring the two photons when they exited led them to behave as if they had been. The unique features of measurement are another wild manifestation of quantum mechanics.

“Quantum mechanics is not difficult, but it’s full of surprises,” Shen said.

The measurement discovery was groundbreaking, but not quite game-changing. That’s because for every 1,000,000 photons, only one pair became entangled. Researchers have since been more successful, but, Shen said, “It’s still not good enough for a computer,” which has to carry out millions to billions of operations per second.

Shen was able to build a two-bit quantum logic gate with such efficiency because of the discovery of a new class of quantum photonic states — photonic dimers, photons entangled in both space and frequency. His prediction of their existence was experimentally validated in 2013, and he has since been finding applications for this new form of light.

When a single photon enters a logic gate, nothing notable happens — it goes in and comes out. But when there are two photons, “That’s when we predicted the two can make a new state, photonic dimers. It turns out this new state is crucial.”

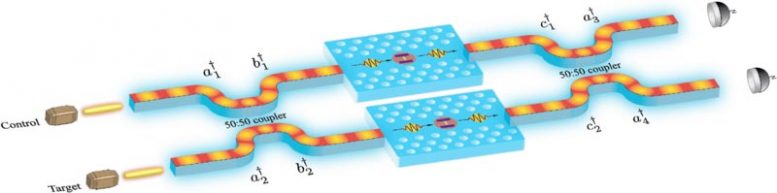

High-fidelity, two-bit logic gate, designed by Jung-Tsung Shen. Credit: Jung-Tsung Shen

Mathematically, there are many ways to design a logic gate for two-bit operations. These different designs are called equivalent. The specific logic gate that Shen and his research group designed is the controlled-phase gate (or controlled-Z gate). The principal function of the controlled-phase gate is that the two photons that come out are in the negative state of the two photons that went in.

“In classical circuits, there is no minus sign,” Shen said. “But in quantum computing, it turns out the minus sign exists and is crucial.”

“Quantum mechanics is not difficult, but it’s full of surprises.”

— Jung-Tsung Shen

When two independent photons (representing two optical qubits) enter the logic gate, “The design of the logic gate is such that the two photons can form a photonic dimer,” Shen said. “It turns out the new quantum photonic state is crucial as it enables the output state to have the correct sign that is essential to the optical logic operations.”

Shen has been working with the University of Michigan to test his design, which is a solid-state logic gate — one that can operate under moderate conditions. So far, he says, results seem positive.

Shen says this result, while baffling to most, is clear as day to those in the know.

“It’s like a puzzle,” he said. “It may be complicated to do, but once it’s done, just by glancing at it, you will know it’s correct.”

Reference: “Two-photon controlled-phase gates enabled by photonic dimers” by Zihao Chen, Yao Zhou, Jung-Tsung Shen, Pei-Cheng Ku and Duncan Steel, 21 May 2021, Physical Review A.DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevA.103.052610

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, ECCS grants nos. 1608049 and 1838996. It was also supported by the 2018 NSF Quantum Leap (RAISE) Award.

The McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis promotes independent inquiry and education with an emphasis on scientific excellence, innovation and collaboration without boundaries. McKelvey Engineering has top-ranked research and graduate programs across departments, particularly in biomedical engineering, environmental engineering and computing, and has one of the most selective undergraduate programs in the country. With 140 full-time faculty, 1,387 undergraduate students, 1,448 graduate students and 21,000 living alumni, we are working to solve some of society’s greatest challenges; to prepare students to become leaders and innovate throughout their careers; and to be a catalyst of economic development for the St. Louis region and beyond.