One of the obstacles for progress in the quest for a working quantum computer has been that the working devices that go into a quantum computer and perform the actual calculations, the qubits, have hitherto been made by universities and in small numbers. But in recent years, a pan-European collaboration, in partnership with French microelectronics leader CEA-Leti, has been exploring everyday transistors — that are present in billions in all our mobile phones — for their use as qubits.

The French company Leti makes giant wafers full of devices, and, after measuring, researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, have found these industrially produced devices to be suitable as a qubit platform capable of moving to the second dimension, a significant step for a working quantum computer. The result is now published in Nature Communications.

Quantum dots in two dimensional array is a leap ahead

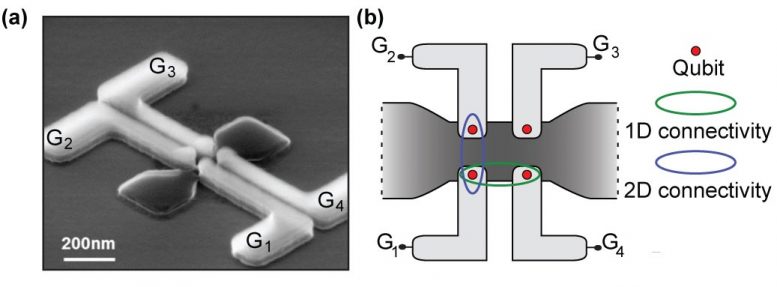

One of the key features of the devices is the two-dimensional array of quantum dot. Or more precisely, a two by two lattice of quantum dots. “What we have shown is that we can realize single electron control in every single one of these quantum dots. This is very important for the development of a qubit, because one of the possible ways of making qubits is to use the spin of a single electron. So reaching this goal of controlling the single electrons and doing it in a 2D array of quantum dots was very important for us,” says Fabio Ansaloni, former PhD student, now postdoc at center for Quantum Devices, NBI.

(a) Scanning electron image of one of the Foundry-fabricated quantum dot devices. Four quantum dots can be formed in the silicon (dark grey), using four independent control wires (light grey). These wires are the control knobs that enable the so called quantum gates. (b) Schematic of the two-dimensional array device. Each Qubit (red circle) can interact with its nearest neighbor in the two-dimensional network, and circumvent a Qubit that fails for one reason or other. This setup is what “second dimension” means. Credit: Fabio Ansaloni

Using electron spins has proven to be advantageous for the implementation of qubits. In fact, their “quiet” nature makes spins weakly interacting with the noisy environment, an important requirement to obtain highly performing qubits.

Extending quantum computers processors to the second dimension has been proven to be essential for a more efficient implementation of quantum error correction routines. Quantum error correction will enable future quantum computers to be fault tolerant against individual qubit failures during the computations.

The importance of industry scale production

Assistant Professor at Center for Quantum Devices, NBI, Anasua Chatterjee adds: “The original idea was to make an array of spin qubits, get down to single electrons and become able to control them and move them around. In that sense it is really great that Leti was able to deliver the samples we have used, which in turn made it possible for us to attain this result. A lot of credit goes to the pan-European project consortium, and generous funding from the EU, helping us to slowly move from the level of a single quantum dot with a single electron to having two electrons, and now moving on to the two dimensional arrays. Two dimensional arrays is a really big goal, because that’s beginning to look like something you absolutely need to build a quantum computer. So Leti has been involved with a series of projects over the years, which have all contributed to this result.”

The credit for getting this far belongs to many projects across Europe

The development has been gradual. In 2015, researchers in Grenoble succeeded in making the first spin qubit, but this was based on holes, not electrons. Back then, the performance of the devices made in the “hole regime” were not optimal, and the technology has advanced so that the devices now at NBI can have two dimensional arrays in the single electron regime. The progress is threefold, the researchers explain: “First, producing the devices in an industrial foundry is a necessity. The scalability of a modern, industrial process is essential as we start to make bigger arrays, for example for small quantum simulators. Second, when making a quantum computer, you need an array in two dimensions, and you need a way of connecting the external world to each qubit. If you have 4-5 connections for each qubit, you quickly end up with a unrealistic number of wires going out of the low-temperature setup. But what we have managed to show is that we can have one gate per electron, and you can read and control with the same gate. And lastly, using these tools we were able to move and swap single electrons in a controlled way around the array, a challenge in itself.”

Two dimensional arrays can control errors

Controlling errors occurring in the devices is a chapter in itself. The computers we use today produce plenty of errors, but they are corrected through what is called the repetition code. In a conventional computer, you can have information in either a 0 or a 1. In order to be sure that the outcome of a calculation is correct, the computer repeats the calculation and if one transistor makes an error, it is corrected through simple majority. If the majority of the calculations performed in other transistors point to 1 and not 0, then 1 is chosen as the result. This is not possible in a quantum computer since you cannot make an exact copy of a qubit, so quantum error correction works in another way: State-of-the-art physical qubits do not have low error rate yet, but if enough of them are combined in the 2D array, they can keep each other in check, so to speak. This is another advantage of the now realized 2D array.

The next step from this milestone

The result realized at the Niels Bohr Institute shows that it is now possible to control single electrons, and perform the experiment in the absence of a magnetic field. So the next step will be to look for spins – spin signatures – in the presence of a magnetic field. This will be essential to implement single and two qubit gates between the single qubits in the array. Theory has shown that a handful of single and two qubit gates, called a complete set of quantum gates, are enough to enable universal quantum computation.

Reference: “Single-electron operations in a foundry-fabricated array of quantum dots” by Fabio Ansaloni, Anasua Chatterjee, Heorhii Bohuslavskyi, Benoit Bertrand, Louis Hutin, Maud Vinet and Ferdinand Kuemmeth, 16 December 2020, Nature Communications.DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-20280-3