Work has potential applications in

The work was reported in the November 3, 2021, issue of the journal Nature.

The demonstration of finite momentum superconductivity in a layered crystal known as a natural superlattice means that the material can be tweaked to create different patterns of superconductivity within the same sample. And that, in turn, could have implications for quantum computing and more.

The material is also expected to become an important tool for plumbing the secrets of unconventional superconductors. This may be useful for new quantum technologies. Designing such technologies is challenging, partly because the materials they are composed of can be difficult to study. The new material could simplify such research because, among other things, it is relatively easy to make.

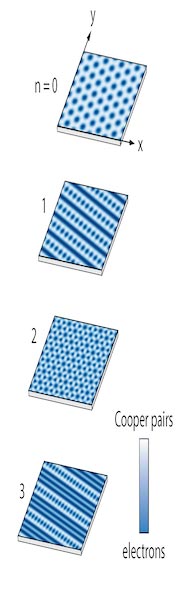

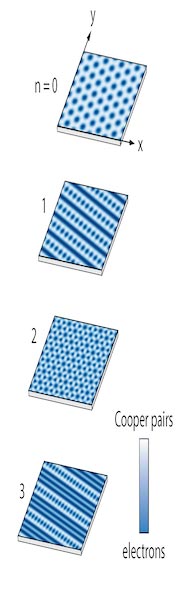

Diagram illustrating three different patterns of superconductivity realized in a new material synthesized at MIT. Credit: Image courtesy of the Checkelsky lab

“An important theme of our research is that new physics comes from new materials,” says Joseph Checkelsky, lead principal investigator of the work and the Mitsui Career Development Associate Professor of Physics. “Our initial report last year was of this new material. This new work reports the new physics.”

Checkelsky’s co-authors on the current paper include lead author Aravind Devarakonda PhD ’21, who is now at

Aravind Devarakonda PhD ’21 is lead author of a paper describing an exotic form of superconductivity. Credit: Denis Paiste

While superconductivity is usually destroyed by modest magnetic fields, a finite momentum superconductor can persist further by forming a regular pattern of regions with lots of Cooper pairs and regions that have none. It turns out this kind of superconductor can be manipulated to form a variety of unusual patterns as Cooper pairs move between quantum mechanical orbits known as Landau levels. And that means, Checkelsky says, that scientists should now be able to create different patterns of superconductivity within the same material.

“This is a striking experiment which is able to demonstrate Cooper pairs moving between Landau levels in a superconductor, something that has never been observed before. Frankly, I never anticipated seeing this in a crystal you could hold in your hand, so this is very exciting. To observe this elusive effect, the authors had to perform painstaking, high-precision measurements on a uniquely two-dimensional superconductor that they had previously discovered. It’s a remarkable achievement, not only in its technical difficulty, but also in its cleverness,” says Kyle Shen, professor of physics at Cornell University. Shen was not involved in the study.

Further, the physicists realized that their material also has the ingredients for yet another exotic kind of superconductivity. Topological superconductivity involves the movement of charge along edges or boundaries. In this case, that charge could travel along the edges of each internal superconducting pattern.

The Checkelsky team is currently working to see if their material is indeed capable of topological superconductivity. If so, “can we combine both new types of superconductivity? What could that bring?” Checkelsky asks.

“It’s been a lot of fun realizing this new material,” he concludes. “As we’ve dug into understanding what it can do, there have been a number of surprises. It’s really exciting when new things come out that we don’t expect.”

Reference: “Signatures of bosonic Landau levels in a finite-momentum superconductor” by A. Devarakonda, T. Suzuki, S. Fang, J. Zhu, D. Graf, M. Kriener, L. Fu, E. Kaxiras and J. G. Checkelsky, 3 November 2021, Nature.DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03915-3

This work was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Office of Naval Research, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science, the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Rutgers Center for Materials Theory.

Computations were performed at Harvard University. Other parts of the work were performed at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, which is supported by the NSF, the State of Florida, and Department of Energy.